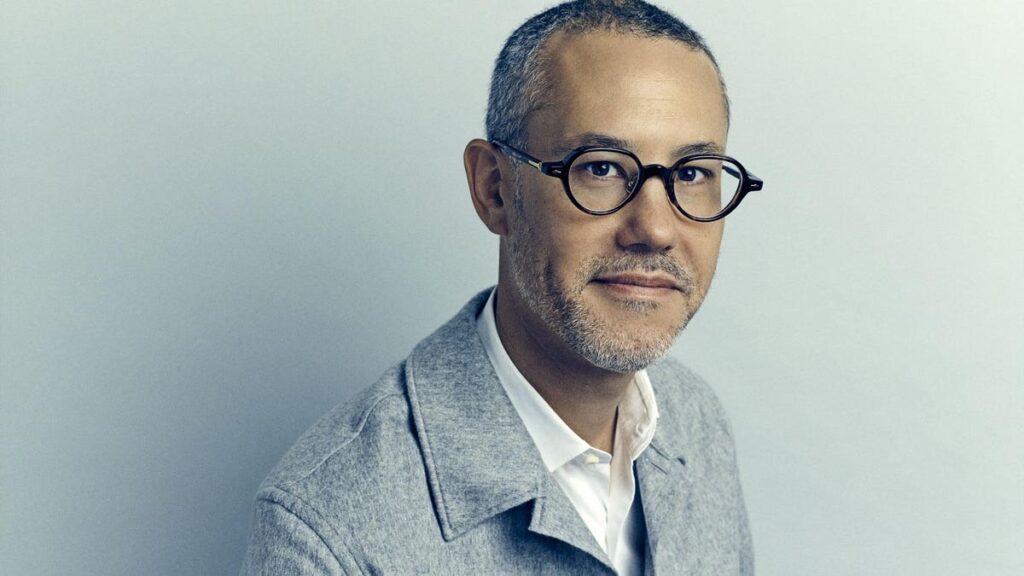

Chris Tsai, son of legendary investor Jerry Tsai, grew up at the feet of Wall Street’s smartest investors. He says he’s driven by fundamentals, but his portfolio’s success tells another story.

By Sergei Klebnikov

When he was just a teenager, Christopher Tsai would telephone the venerated chief executive of Bear Stearns, Ace Greenberg, to ask why he was buying different stocks like oilfield services giant Schlumberger. Greenberg personally managed money for some of Tsai’s family at the time—including a custodian account that Christopher’s parents had set up for him.

“It drove him crazy—I was the only 16-year-old that would call him up and bug him on his direct line to the trading floor,” recalls Tsai, now 48, who is the son of Wall Street titan Gerald Tsai, who helped build Fidelity Investments in the 1960s, then became the hottest hand fund manager with his Manhattan Fund, and later turned American Can into the financial powerhouse Primerica.

Now Christopher Tsai is a money manager himself, with a quarter of a century’s experience behind him, and he’s having a hell of a year. His focused $111 million portfolio of mostly large-cap growth stocks is up 49.5% (versus just under 19% for the S&P 500) so far this year, led by Tesla, Apple and Costco. It’s a big turnaround from 2022 when his fund was down 50%.

Tsai grew up in Greenwich, Connecticut in the early 1980s, surrounded by well-trimmed hedges, elegant dinner parties and talk of markets and dealmaking. His mother was the second of Tsai’s four wives. Many of his father’s friends were larger-than-life figures on Wall Street, including the likes of hotelier and entertainment magnate Laurence Tisch, Norman E. Alexander, who transformed a printing ink company into aerospace conglomerate Sequa, and Greenberg.

“I was very fortunate to be surrounded by so many interesting CEOs and have the opportunity to learn from them from a very young age,” recalls Tsai sitting in the NYC offices of Tsai Capital, which he launched in 1997 with just $3 million in mostly family money.

Unsurprisingly, Tsai developed an interest in the stock market before he was a teenager, knowing then that he wanted to manage money. He bought his first shares with leftover gardening earnings and was hooked as soon as he saw he had made a small profit. “I would regularly rush home from school to read the latest edition of Value Line,” he tells Forbes.

Christopher’s father, Jerry Tsai, rose to fame working for Boston mutual fund giant Fidelity in the 1950s and 60s where he pioneered momentum growth stock funds. He famously bought hot stocks like Xerox, IBM and Polaroid as the market swooned during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. That year his Fidelity Capital Fund was up 110% versus about 33% for the S&P 500. In 1966 he left Fidelity to start his own mutual fund, the Manhattan Fund and it quickly became the biggest fund on Wall Street, with some $430 million in assets by 1967. He later became known as a shrewd dealmaker, running American Can and becoming the first Chinese-American to head a member of the Dow Jones industrials. Eventually he merged American Can with investment bank Smith Barney and created Primerica. Tsai sold Primerica to billionaire Sandy Weill’s Commercial Credit for $1.8 billion in 1988 and it eventually merged with Citigroup.

Investing runs in the family. Ruth Tsai, Chris’ grandmother, was the first woman to trade shares on the floor of the Shanghai Stock Exchange, finding an opening during World War II. Christopher Tsai says he has drawn from the wisdom of two previous generations and incorporated many of those ideas into his own investing philosophy. “My father was very much a momentum guy—I’m much more fundamentally based,” says Tsai.

Christopher’s father, Wall Street titan Gerald Tsai, helped build Fidelity Investments in the 1960s and later turned American Can into the financial powerhouse Primerica.

Daniel Acker/Bloomberg

However, if you look at Tsai’s recent market-crushing returns, they come mostly from mega cap stocks like Tesla, Apple and Costco, which reside firmly in the momentum camp. Tsai says his overriding philosophy is to invest in high-quality companies that are typically asset-light, have long-term growth prospects and durable competitive advantages. “One piece of advice from my father that stands out is, ‘always position yourself with the wind at your back’,’” says Tsai. “I think about that as positioning yourself on the right side of change—that means investing in innovation, disruption, scalable technologies and businesses that are run by excellent leaders.”

That approach seems to be paying off this year, with his strategy solidly rebounding from last year’s downturn. “Valuations have corrected to a more normalized level after being overly punished in 2022,” says Tsai.

Over the last five years, his strategy has produced annualized returns of 12.3% after fees, outpacing the S&P 500’s roughly 11% return. Since his long-only fund’s inception in 2000, it has returned 7.6% net of fees versus 6.9% for the benchmark. A $100,000 invested with Tsai starting in 2000, that would have grown to $551,200 versus about $471,300 for the S&P 500.

When I told my late father, ‘I’m going into money management, ‘he said, ‘That’s great but you’re on your own, you need to build the business on your own,” recalls Tsai.

After graduating from Middlebury College in 1997—majoring in philosophy and international politics–Tsai moved to Manhattan and began to build his business little by little. At first running his firm out of his apartment on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, Tsai admits that there was some trial and error.

Luckily, he had experience to draw from. In the summers prior, he had already honed his skills interning with veteran money managers Mario Gabelli and John A. Levin. Even in his teenage years, Tsai had given out investment advice and sometimes managed small amounts of money for family friends.

One of those “clients” was the owner of a Chinese restaurant in Greenwich; Tsai was a regular with his order of orange beef on the way home from work. After getting to know each other, the owner entrusted him with his life savings of around $400,000. “Fortunately, I did very well for him—he became one of my first clients after I started my firm,” says Tsai.

Today Tsai’s investors are predominantly high net worth individuals and family offices, though Tsai also manages money for corporations and charitable foundations as well as some retail customers with modest portfolios. “Like us, our clients have a long-term time horizon—in many cases we’re managing generational wealth,” he says. “They understand that we can typically create the most value for them during market sell-offs and they usually give us more firepower to act during those times.”

“One piece of advice from my father that stands out is, ‘always position yourself with the wind at your back.’”

Tsai cites a somewhat odd pairing of Berkshire Hathaway value-loving vice chairman Charlie Munger and growth stock mutual fund magnate Ron Baron as two of his role models when it comes to investing. He typically likes to invest in profitable businesses with proven track records of allocating capital, or those that are at their earliest inflection points. One example is Mastercard (MA), which he bought shares of almost immediately after it went public in 2006. “It was clear to me that the company was a duopoly along with Visa… It was also clear to me that there was so much potential to increase margins and that the world was only in its infancy in its move to a cashless society,” he says. In terms of fundamentals, he focused on the company’s mid-teens price-to-earnings ratio, which struck him as very reasonable at the time for such a long runway of growth. When Visa later went public, it did so at a much higher valuation, he points out. Tsai also frequently taps into his ample network of Wall Street contacts in an effort to test his investment thesis.

“We do a lot of work up front, wait for an opportunity, typically a market sell off, and then we swing hard,” he says. Tsai owns just 21, mostly large-cap companies, which he says allows for enough diversification to participate in different areas of the economy while still maintaining a focused portfolio. “We go in with the idea that we want to own these businesses indefinitely—it forces us to really choose.”

His top holding is a $35 million stake in Tesla (TSLA). While Tsai had been following Elon Musk’s electric-vehicle maker for many years, he did not consider investing until the company turned profitable at the end of 2019. He took an initial position in Tesla the following February, and as the stock fell during the Covid-induced market crash, he continued to buy on the way down.

That investment has paid off roughly fivefold, Tsai says. He cites the company’s massive competitive advantage, culture of innovation and strong track record of reinvesting capital—even in a higher rate environment. Shares of Tesla have been on a tear this year, more than doubling by late August. “Tesla had all the characteristics we look for in a business and they were misunderstood—and still are misunderstood—by Wall Street,” says Tsai.

Another top holding, Costco (COST), which he likes because the retailer is a great example of economies of scale, taking advantage of its sheer size to keep costs low and pass the savings onto customers. Tsai owned just over 7,700 shares of Costco stock at the end of June, currently worth about $4.1 million.

Tesla and Apple (AAPL), another top holding, also take advantage of their size to bolster profitability over the long run. Tsai first bought Apple shares at a discount after the stock dipped in 2016 and has held onto them since; It was Tsai’s second-largest holding by dollar value (roughly $18 million). The stock has also been another driving force behind his strategy’s strong returns so far in 2023, rising over 40% so far this year.

Circling back to his core philosophy of “being on the right side of change” when it comes to investing, Tsai has also been buying into what he calls indirect beneficiaries of Artificial Intelligence. “I’m not telling anyone anything new when I say that AI is very much like the new California Gold Rush—but it wasn’t the gold digger that made money, but the companies that sold the picks and shovels.” He argues that the big cloud service providers—Amazon, Google and Microsoft—are going to be in that camp: “Their cloud infrastructure is akin to the railroads of the past, and there’s going to be more data and analytics flowing over that,” says Tsai.

Other big holdings in Tsai’s portfolio include nearly $2.8 million worth of athletic wear giant Nike (NKE) shares, $3 million worth of cloud-computing company Snowflake (SNOW), $3.2 million worth of commercial real estate information and analytics firm CoStar Group (CSGP) and $2.9 million worth of IDEXX Labs (IDXX), a $3.4 billion (revs) company that makes diagnostic tests for veterinarians. Nearly all of his holdings sport rich valuations in terms of price-to-sales and price-to-earnings.

“Tesla had all the characteristics we look for in a business and they were misunderstood—and still are misunderstood—by Wall Street.”

Tsai’s most recent addition is Columbus, Ohio-based Mettler-Toledo International (MTD), a global manufacturer of laboratory and other precision instruments. Shares are down roughly 15% so far this year and are flat over the last 12 months. Still, the company has more than 5,000 sales and service reps around the world and revenue and operating income have increased annually for the last five years, reaching $3.9 billion and $1.13 billion, respectively, by the end of 2022.

While markets remain caught up with the Federal Reserve’s next move when it comes to interest rates, the best way to offset inflationary concerns, Tsai argues, is to invest in high quality equities that are growing rapidly and who themselves can pass on price increases to the consumer.

When it comes to markets, Tsai says it’s normal as humans not to like uncertainty. But as he tells clients, thinking long term is always beneficial. Even in bull markets there are pockets of mispricing where quality businesses are trading at a discount, he adds. “So we’re always looking for those pockets of mispricing that might not be so obvious.”

“I tell clients not to forego investing just because of short term concerns,” says Tsai. “You know, since I started investing money over 20 years ago, the news has never really been good… There’s always something to be concerned about, but that’s our opportunity.”