In some ways the covid-19 pandemic was a blip. After soaring in 2020, unemployment across the rich world quickly dropped to pre-pandemic lows. Rich countries reattained their pre-covid gdp levels in short order. And yet, more than two years after lockdowns were lifted, at least one change appears to be enduring: consumer habits across the rich world have shifted decisively, and perhaps permanently. Welcome to the age of the hermit.

In the years before covid, the share of consumer spending devoted to services rose steadily upwards. As societies got richer, they demanded more in the way of luxury experiences, health care and financial planning. Then, in 2020, spending on services, from hotel stays to hair cuts, collapsed owing to lockdowns. With people spending more time at home, demand for goods jumped, with a rush for computer equipment and exercise bikes.

Three years on the share of spending devoted to services remains below its pre-covid level (see chart 1). Relative to its pre-covid trend, the decline is even sharper. Rich-world consumers are spending on the order of $600bn a year less on services than you might have expected in 2019. In particular, people are less interested in spending on leisure activities that generally take place outside the home, including hospitality and recreation. The money saved is being redirected to goods, ranging from durables such as chairs and fridges, to things like clothes, food and wine.

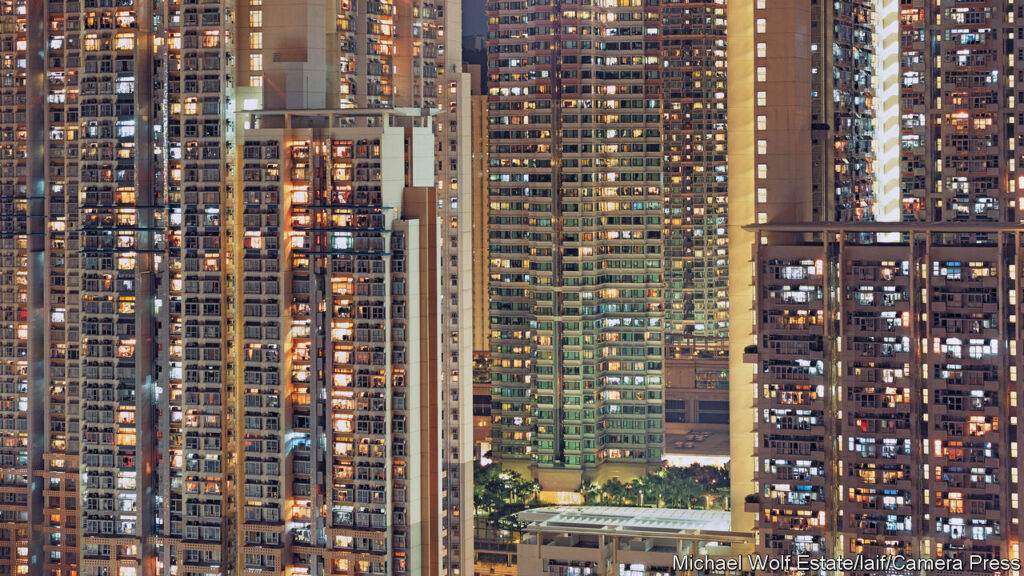

In countries that spent less time in lockdown, hermit habits have not become ingrained. Spending on services in New Zealand and South Korea, for instance, is in line with its pre-covid trend. Elsewhere, though, hermit behaviour now looks pathological. In the Czech Republic, which was whacked by covid, the services share is about three percentage points below trend. America is not far off. Japan has witnessed a 50% decline in restaurant bookings for client entertainment and other business purposes. Pity the drunk salaryman staggering around Tokyo’s entertainment districts: he is now an endangered species.

At first glance, the figures are hard to reconcile with the anecdotes. Isn’t it harder than ever to get a reservation at a good restaurant? And aren’t hotels full of travellers, causing prices to soar? Yet the true source of the crowding is not sky-high demand, but constrained supply. These days fewer people want to work in hospitality—in America total employment in the industry remains lower than in late 2019. And the disruption of the pandemic means that many hotels and restaurants that would have opened in 2020 and 2021 never did. The number of hotels in Britain, at around 10,000, has not grown since 2019.

Firms are noticing the $600bn shift. In a recent earnings call an executive at Darden Restaurants, which runs one of America’s finest restaurant chains, Olive Garden, noted that, relative to pre-covid times, “we’re probably in that 80% range in terms of traffic”. At Home Depot, which sells tools to improve your home, revenue is up by about 15% on 2019 in real terms. Investors are noticing. Goldman Sachs, a bank, tracks the share prices of companies that tend to benefit when people stay at home (such as e-commerce firms) and those that thrive when people are out and about (such as airlines). Even today, the market looks favourably upon firms that service stay-at-homers (see chart 2).

Why has hermit behaviour endured? The first possible reason is that some tremulous folk remain afraid of infection, whether by covid or something else. Across the rich world people are swapping crowded public transport for the privacy of their own vehicles. In Britain, car use is in line with the pre-covid norm, whereas public-transport use is well down. People also seem less keen on up-close-and-personal services. In America spending on hairdressing and personal-grooming treatments is 20% below its pre-covid trend, while spending on cosmetics, perfumes and nail preparations is up by a quarter.

The second relates to work patterns. Across the rich world people now work about one day a week at home, according to Cevat Giray Aksoy of King’s College London and colleagues. This cuts demand for the services bought when at the office, including lunches, and raises demand for do-it-yourself goods. Last year Italians spent 34% more on glassware, tableware and household utensils than in 2019.

The third relates to values. The pandemic may have made people genuinely more hermit-like. According to official data from America, last year people slept about 11 minutes more than they did in 2019. They also spent less on clubs that require membership and other social activities, and more on solitary pursuits, such as gardening, magazines and pets. Meanwhile, global online searches for “Patience”, a card game otherwise known as solitaire, are running at about twice their pre-pandemic level. Covid’s biggest legacy, it seems, has been to pull people apart. ■